Validation. Only so much of a design's success can be determined at the drawing table. It's only when the design becomes material that we can gauge it's ultimate success. In this case, as I hope will be the trend with the Daulton project, we got it. This part of the project is already successful as a stand alone sculpture installation, a thing made possible in period construction because the material pallet is made up of only a handful of organic materials that are inherently pleasing to the eye at any point during the construction process.

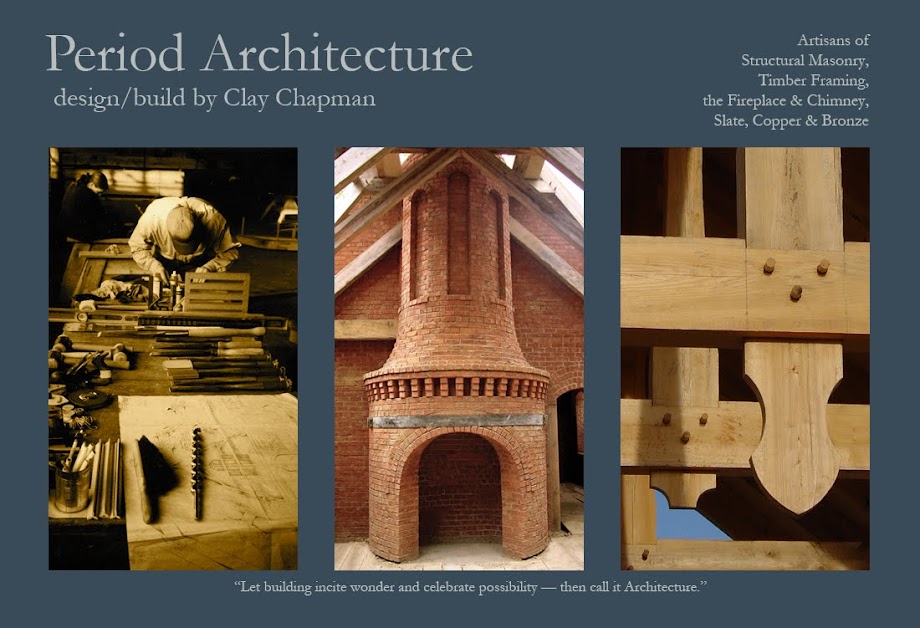

Validation. Only so much of a design's success can be determined at the drawing table. It's only when the design becomes material that we can gauge it's ultimate success. In this case, as I hope will be the trend with the Daulton project, we got it. This part of the project is already successful as a stand alone sculpture installation, a thing made possible in period construction because the material pallet is made up of only a handful of organic materials that are inherently pleasing to the eye at any point during the construction process. The traditional, or period, approach to building has a raw truth about it that is unapologetic when it comes to distilling beauty. Combining the traditional and the conventional processes into a hybrid building process is a reasonable compromise to the current "snap together" design/build dilemma.

(Point of nomenclature : "traditional" is often used when "conventional" is intended.)

The Pierce/Lee House, linked from the home page of the Period Architecture website to "architecture" is a great example of pure traditional construction. The Elias Cottage also featured under "architecture" is an example of hybrid construction. This refers to the combination of historic process with modern building techniques in which case, 20% or so of the design is strategically allocated to a period format and the remaining portion of the design conventional built.

It should be of no surprise, that in period design, as with modern architecture, there is ground breaking potential. It's always important not to simply rehash what's already been done. A blues musician is not limited to covering classic blues standards, but may, and should, sing his own song if it's in him. Likewise, traditional types of architecture are often given a regard that requires unalterable, unnatural adherence, though it was through creative alteration that all architectural types came to exist to begin with. There may be an underlying suspicion in the collective (especially in the academic view of period architecture) that we are unable to expound; unable to do anything of creative significance because the era of modern manufacturing, in all it's efficiency, has made the artisan tradesman obsolete; and in so doing extinguished that brazen creativity we Americans pride ourselves as being descended. And now we scurry about snatching up the remnants of our honest ancestors in hopes of staking an identity claim on something meaningful and real. There is some validity to the panic and of course this is in no way limited to creative building — what car being built today will be held with the same affection as a 66 Ford Mustang in the year 2060.

All this to say, a penchant for period architecture should in no way be based on an unbalanced appreciation for another time. Many modern architects view period design with a bricker-brack sort of kitchy, collectibles mentality and there is good fodder for this. But it's not so much a particular period I'm drawn too, as a few rudimentary materials that happen to be historically ubiquitous; materials I find difficult to improve upon without a price.

What we build should be immediately relevant, period or not. While celebrating history, traditional building should also embrace posterity and prioritize legacy. The Daulton design does this. As pictured above, the progress feels like the restoration of a ruin, while affecting modern characteristics that make it relevant to our time.

In period construction, the window of interpretation at the scaffold plays a big part in the building process and can make or break the intentions of a designer. Conventional building on the other hand dismisses the tradesman's interpretation. There is incredible economic advantage to this: tradesmen may be less skilled, materials are streamlined to points of specific application, and you can always count on the same result. In either case, and without sniping, you get what you pay for.